In recent years, we’ve seen a lot of early RPGs, such as Traveller and Runequest, resurrected in new editions with cleaner rules and more modern presentations which, for the most part, have retained the original feel of the game. Chivalry & Sorcery has seen several editions over the years, the last almost 20 years ago in 2000 (not counting the 2011 “Essence” release which was only 44 pages). Now, following a successful Kickstarter, a new 5th Edition has returned at a whopping 602 pages. Here is a little history and some thoughts on the first-reading of this new version.

History

Chivalry & Sorcery is a fantasy role-playing game that was originally created by Canadian designers Edward E. Simbalist and Wilf K. Backhaus in 19761. They were dissatisfied with the lack of realism in D&D and created a gaming system derived from it, which included copious amounts of detail on medieval life, named Chevalier. They intended to present it to Gary Gygax at Gen Con IX in 1976 but changed their minds once Simbalist saw Gygax arguing with a staff member and decided he didn’t like the “vibe” he got from the encounter.

Then, by sheer luck, they met Scott Bizar who offered to publish it through his company, Fantasy Games Unlimited (FGU) whose only RPG so far was Dennis Sustare’s Bunnies & Burrows. After some final changes to get rid of the last remnants of D&D and make the game safe for publication from a copyright point of view, Simbalist and Backhaus published the first edition of their game - now renamed Chivalry & Sorcery - shortly after the release of the first edition Advanced D&D Monster Manual.

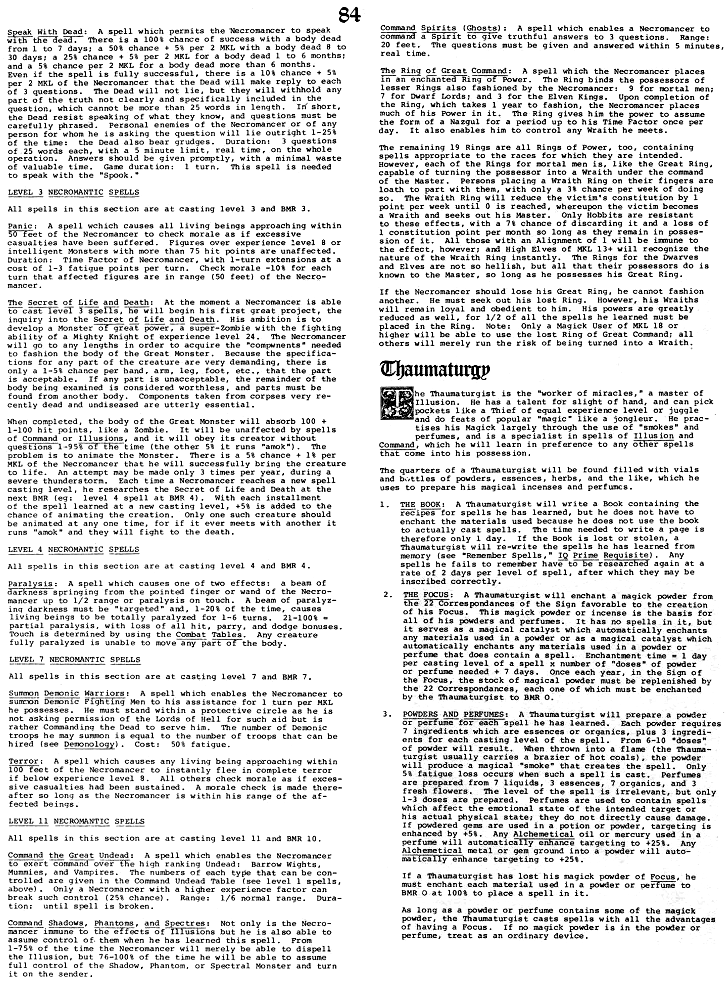

The first edition, nicknamed the “Red Book”2 by fans, was not only a role-playing game but an epic treatise on life in medieval Europe, and used photo reduction to fit four pages of text onto each page, making it complete and concise but a little hard to read.

A page from C&S 1st Edition

Rules were included for character creation, combat and magic, Knights (tournaments, courtly love, fiefs, political influence), a hierarchical priesthood who could perform miracles, a large section on monsters, including the Infernal Court of demons and even wargames rules for armies. In addition to ideas taken from Arthurian myth, the first edition also incorporated elements of J. R. R. Tolkien such as hobbits and balrogs, although these references disappeared in subsequent editions for reasons of copyright. Notably, the game did not focus much on dungeons which gently cajoled players into running adventures with actual plots.

Published game worlds were pretty rare in the 1970’s, but C&S had three: the Northern/Nomadic world of Swords & Sorcerers (1978), a mythical England described in Arden (1979), and a dinosaur-era world detailed in Saurians (1979). Judges Guild had started to publish adventures for other games around that time but C&S had virtually none because Scott Bizar thought they were irrelevant and players and GMs would prefer to create their own.

The second edition, released in 1983, was presented in a cardboard box containing three rules booklets, with greatly improved presentation. The text was larger, lighter and more concise and there was a tendency towards greater consistency in the organization of the rules. There were no fundamental changes as compared with the first edition, but those changes were intended mostly to clarify or simplify some points in the rules.

After the relative success of the second edition, C&S sank into obscurity for over a decade, mainly due to the lack of support from Fantasy Games Unlimited (FGU). The game was finally reissued in a third edition in 1996 by Highlander Designs (HD), an American publishing house founded by GW Thompson. The authors were again Ed Simbalist and Wilf Backhaus along with GW Thompson. In contrast to previous editions, this edition strayed quite far from previous historical accuracy and was much more of a fantasy role-playing game. The magic system was greatly simplified, losing a lot of its earlier flavor along the way, but it did introduce the Skillskape system of talents and skills which would re-emerge in the new 5th edition. Support for the game was better, with several supplements (a bestiary, GM handbook & screen, the game world of Marakush) published over the following few years.

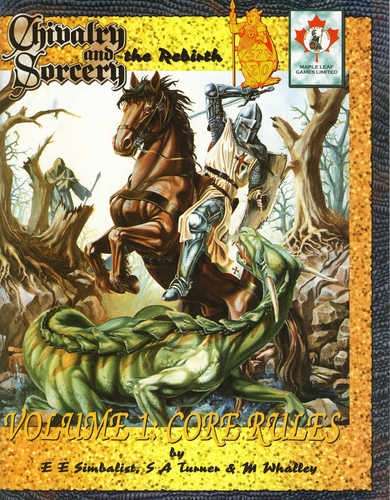

Highlander Designs subsequently went bankrupt and was bought by Brittannia Game Designs Ltd, a company based in England (actually in my old home-county of the West Midlands) and directed by Steve Turner. The fourth edition of C&S, called “The Rebirth” was born a few months later in 2000. The result was the return of some medieval references and some gameplay mechanics (such as “bash” or “Targeting” for spells) and adding back a degree of realism that was lacking in the previous edition. Moreover, many additions to the rules (such as “Laws of Magick”) brought the flavor of the old Magick system back to the game.

|

|

|

|

Kickstarter and 5th Edition

The new 5th Edition was funded on Kickstarter in June 2019 and received a modest but sufficient £32,863, missing only one stretch goal (a complete miniature battles system). The “first printing” PDF was released for general distribution in December 2019.

This edition returns to the earlier days of being a thick tome with detail everywhere. Its 602 pages (including covers) include essays on life in Medieval England & Europe, the Core Rules (including the “Skillskape” system from the 3rd edition), Character Creation, Skills & Vocations (classes but not classes), the Marketplace (goods & equipment), Combat, Magick (the “k” version), Religion and advice for the Gamemaster on creating and running a medieval fantasy world. It also includes a six (yes, six) page character sheet which, trust me, you will use almost every page of.

From the subject and density of the content alone, it’s clear that the writers were 1st edition players and/or fans. The depth of information on how medieval England worked, and what that means for the characters inhabiting that world, would fill a small history book and the game system (particularly character creation) is designed to match. A nice surprise, and of particular interest to me, is the use of The Fief Of William Fitzansculf as an example of a medieval demesne - I was born in Birmingham, U.K., and have lived or worked in most of the settlements mentioned (their modern day equivalents of course, I’m not that old).

As the Daoist sage Laozi said, “The longest journey begins with a single step,” and like all beginnings, the initial step is fundamental. The process of character creation is the very structure underpinning a Player Character (PC), and on which future adventures are laid. - pp51

Character creation is a complex but evocative affair and you will come out of it knowing pretty much every aspect of your character and their background. Its general format hasn’t changed much between editions, but this edition welcomes back some of the more complex aspects in the 100 pages or so dedicated to the task - your Session 0 will not be over in an hour. It’s clear that fighters, specifically knights, along with priests and mages get more attention than other vocations, but some space is given over to thieves, physicians and foresters (amongst others) as lesser vocations. Along the way your character may learn about farming and brewing beer as well. Other races, such as Dwarves and Elves (now firmly divorced from their Tolkien origins) are present but the emphasis is clearly on Humans by default.

In Chivalry & Sorcery, combat revolves around the 15-second Combat Round and the spending of Action Points to carry out actions. - pp268

Combat takes up another 80 odd pages and makes full use of Skillskape for fights with options other than “I roll to hit”. I particularly like the Action Point system which governs not only how much a character can do in a 15 second combat round but simultaneously acts as a form of initiative as well. Fights include active defenses (weapon parry, shield block, dodge) and passive defenses (mostly shield) along with optional tactics (bash, flight, retreat, stand, keep distance, etc), and the old system of trading blows is back as well. Injuries result in the loss of Fatigue and/or Body points, but there’s also Shock, Bleeding and permanent injuries to worry about. It’s not easy to die (after all, you have a lot of background invested in that character) but it’s not that hard either.

Magick was real, very real to the medieval mind and was viewed as demonic. In C&S we view Magick as the ability of someone who has studied ancient texts and learned to access the Universe and coerce Spirit to bend the will of the universe to their desires, rather than petition higher powers as in Religion. - pp288

Magick falls somewhere between D&D and Tolkien. Mages must choose their Mode of Magick, which essentially decides the type of mage they are: Conjuror, Diviner, Enchanter, Hex Master, Necromancer, etc. The whole system is designed around the concept of resistance to the reality-altering effects of magic: if you want to enchant an item, you must overcome the resistance of the materials (which may take several weeks or months); if you want to cast a spell, you have to overcome the resistance of the spell to learn it then the resistance of the target to, well, “target” it, and so on. Casting is actually the easiest part.

While it’s possible to cast spells on-the-fly (say, in combat), and even to make up spells on-the-spot, mages really excel when they have the time (minutes to days or weeks) to cast bigger spells. Want a tornado to wipe out your opposing army? No problem, you just need plenty of warning. There’s no forgetting of spells once they’re cast (I hate Vancian Magic) but it does cost fatigue and/or body to cast or enchant, and that can kill in the long run. Luckily, mages can get help by carrying out their rituals in special places or by drawing on the abilities of apprentices and other mages for the big enchantments.

There’s also not much stopping a mage from learning to fight, other than the fact they’ll be burning valuable spell development time swinging weapons around.3

A ‘miracle’ is the Divine response to the plea, “Oh, great and powerful Divine Being . . . DO SOMETHING!” - pp447

Religion is presented in similar detail, but whereas mages must study to progress their art Priests must profess and practice their Faith in order to perform priestly magicks such as healing or purifying food & water, all the way up to Greater Miracles such as parting seas. Christianity is the default religion presented, but Judaism and Islam also feature heavily, so playing a Muslim cleric from the Holy Land wouldn’t be a problem.

The Kingdom of Cockaigne is formed of a number of landholders, one of whom is Sir Nemo. He maintains a Large Fortified Manor House V (LFMH 5) and has sub-tenants holding a Small Fortified Manor House II (SFMH II) and eight Small Fortified Manor House I (SFMH I).

The chapters on building a campaign world essentially comes down to creating a medieval fiefdom and populating it with NPCs. It would certainly be possible (and probably quite fun) to have a group of characters based around a Lord’s holding and to actually run the estate over long periods of time. Such a campaign is made more useful by the fact that characters can advance not only by earning Experience Points but also by learning and training in their downtime - mages in particular.4

The final chapters cover NPCs and the Bestiary. I did notice an emphasis on natural creatures, undead and the fae (faeries, including goblins, the sidhe and faerie beasts), but while the creatures covered are focused on those found in medieval European folklore their statistics are simple enough that conversion of “fancier” creatures from other games wouldn’t be too hard - although I think the flavor of the game would suffer if some of the more “exotic” D&D creatures are used.

TLDR

C&S 5th Edition goes back to the days of a chunky tome by adding back a lot of the medieval detail lost in some earlier editions. The game system itself has elements from those previous editions but is cleaned up and well presented. I did note a few typos and inconsistencies, although they were slightly annoying to my pedantic tastes rather than actually interfering with gameplay.

The thing that took me by surprise with the PDF is that pretty much everything is hyper-linked, which sounds like a good idea but I often found that an inadvertent click or touch would send you whipping hundreds of pages through the book with no way back if you couldn’t remember where you were. The PDF index is, however, spot on. A less busy, graphically speaking, version would also make page loads a little faster.

Typical dungeon-bashing is possible, but where C&S excels is in the creation of a detailed medieval environment, such as a fief or kingdom, where the players have key roles in managing and protecting their holdings.

If you’re an old (age and time spent playing) C&S player then you’ll recognize a lot and welcome the changes, but the system remains pretty crunchy so you will need to be a dedicated player to stick with it and get the most out of it. This is not a game you’re going to play over a single session when only one person has the book.

-

Coincidentally, C&S is based on Medieval Europe and I’m from the U.K. - the area used as an example of a medieval fiefdom. Ed Simbalist was from Edmonton, Alberta and Wilf Backhaus from Calgary, Alberta. I now live just outside Calgary. ↩︎

-

The “Red Book” is still available online as a PDF - if you can find it - in an unauthorized edition compiled from not only the original Red Book itself but several of its supplements, by fans. Its last incarnation (that I know of) was the 7th edition, and clocked in at an enormous 964 pages. ↩︎

-

The mage in our old C&S campaign, Karsten, was a fierce swordsman - better than a lot of the fighter PCs in the campaign and well able to hold his own against multiple opponents in a fight. The only reason he learned to fight was that he didn’t want to burn off fatigue casting “little” spells, he’d save that for the army-wiping-out spells. ↩︎

-

A quick shout out here to Adrian Hall, an old friend of mine who ran a multi-year C&S 1st edition campaign based in his own world of Aquilande. I forget how many years we played that game, but it covered a fair time IRL and decades in game. In that time we died (a lot, but somehow the gods always wanted us to come back for more), took a whiz miles high off the edge of the Bridge of the Gods, defeated more than one Daughter of the demon Gwy’stil, watched Karsten the Mage (actually, he was a Necromancer, but we didn’t talk about that because he was a friend) build the tower that withstood the assault of several armies (because of the aforementioned necromancy) and passed on our holdings to at least one generation of our children (two in one case). ↩︎